Introduction

It’s been a year since we conducted a comprehensive review of generating capacity across the island. Here is an update on what we have found in 2024 after going through publications from the following entities:

- EirGrid

- ESB Networks (ESBN)

- System Operator for Northern Ireland (SONI)

- Single Electricity Market Operator (SEMO)

We have also reviewed documents related to the Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (RESS) and Enduring Connection Policy (ECP).

Summary

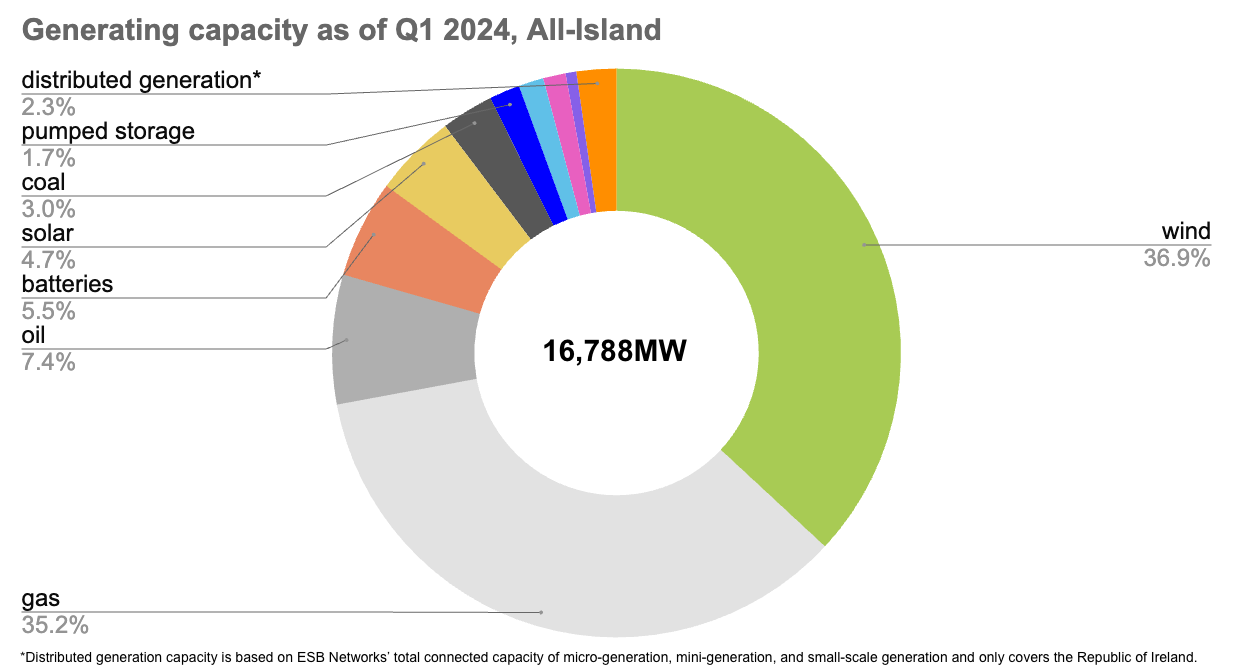

As of March 2024, the island of Ireland has 16.8GW of capacity: 13GW in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) and 3.8GW in Northern Ireland (NI). The breakdown of capacity by type is shown below; wind is the highest at 6.2GW, followed by gas at 5.9GW.

In addition to utility-scale generators, the exhibit below also covers distributed capacity. In 2023, ESB Networks started providing quarterly status updates on micro-generation and mini-generation. By the end of Q1 2024, there are 88,574 micro-generation connections in ROI - essentially rooftop solar - amounting to 346MW of connected capacity.

Exhibit 1: All-island generating capacity, as of Q1 2024

Source: Green Collective, EidGrid, ESBN, SONI, SEMO

Source: Green Collective, EidGrid, ESBN, SONI, SEMO

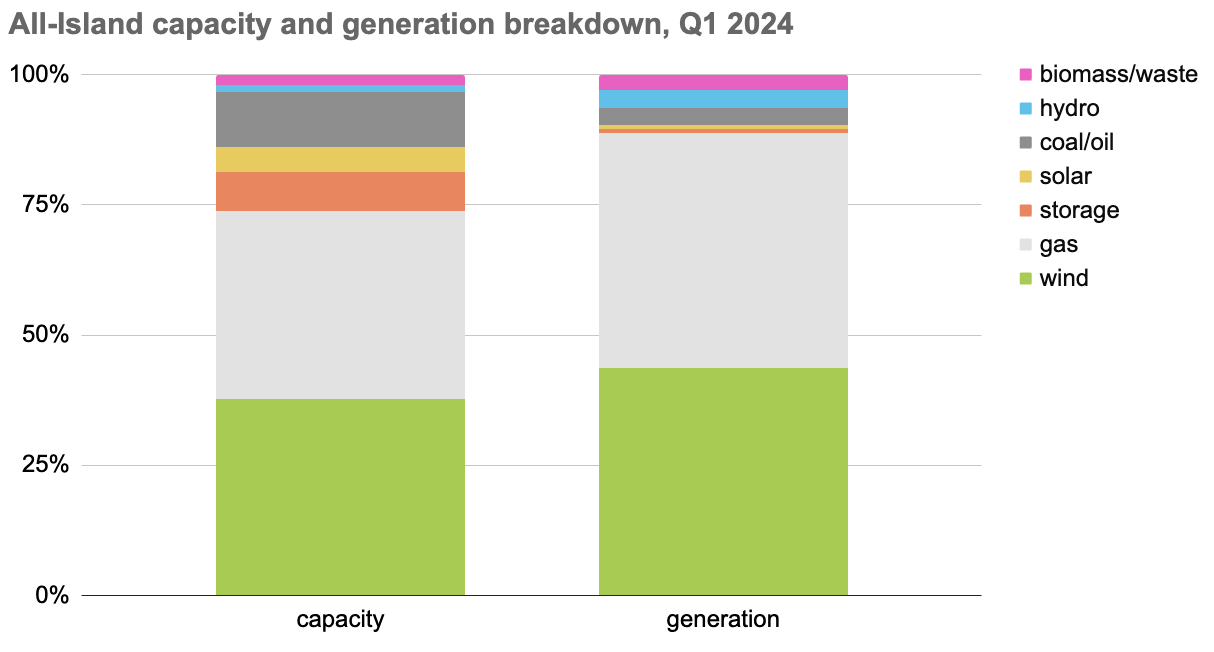

The share of capacity doesn’t necessarily translate into a generator type’s share in generation. For example: while there is over 1GW of capacity where the primary fuel is oil, oil generation is low since these plants are only used as peaker units. Below is a chart comparing, side-by-side, each type’s share in capacity vs. generation.

Exhibit 2: All-island capacity and generation breakdown, Q1 2024

Source: Green Collective, EidGrid, ESBN, SONI, SEMO

Source: Green Collective, EidGrid, ESBN, SONI, SEMO

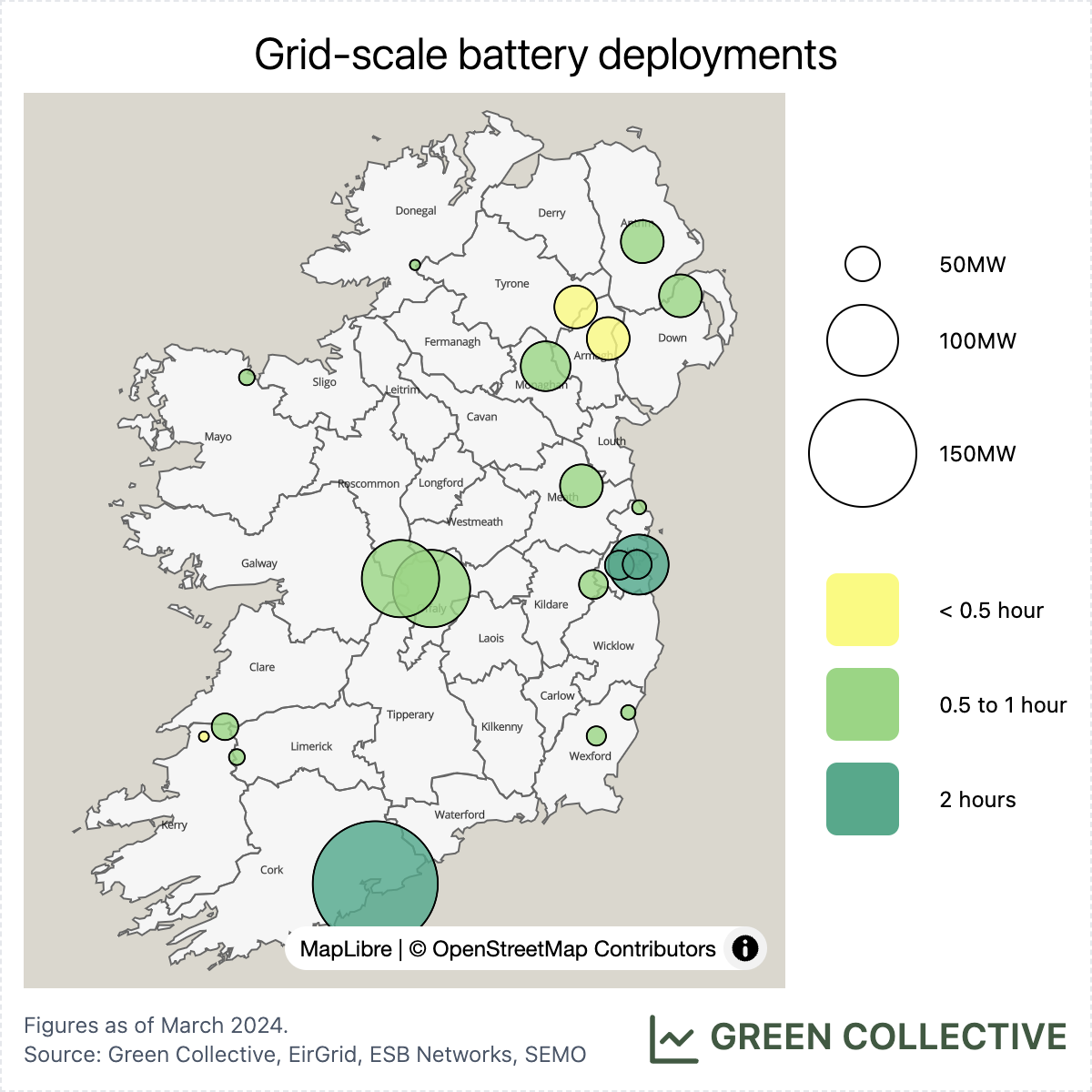

Battery storage

There is now 931.5MW/987MWh of grid-scale battery energy storage across the island. While the duration of these batteries is on the shorter side, some have started discharging during early evening hours to meet peak demand (more details in our November 2023 report). It’s also important to point out that batteries also play a crucial role in providing frequency response: an essential service to ensure grid stability, especially when the system is flooded with inverter-based renewable sources like wind and solar.

Battery chemistry doesn’t determine the duration of energy storage deployments, but costs do. As costs of batteries continue to decline - despite a slight bump in 2022 - we can expect new batteries deployed to have a longer duration.

Exhibit 3: All-island grid-scale battery deployments

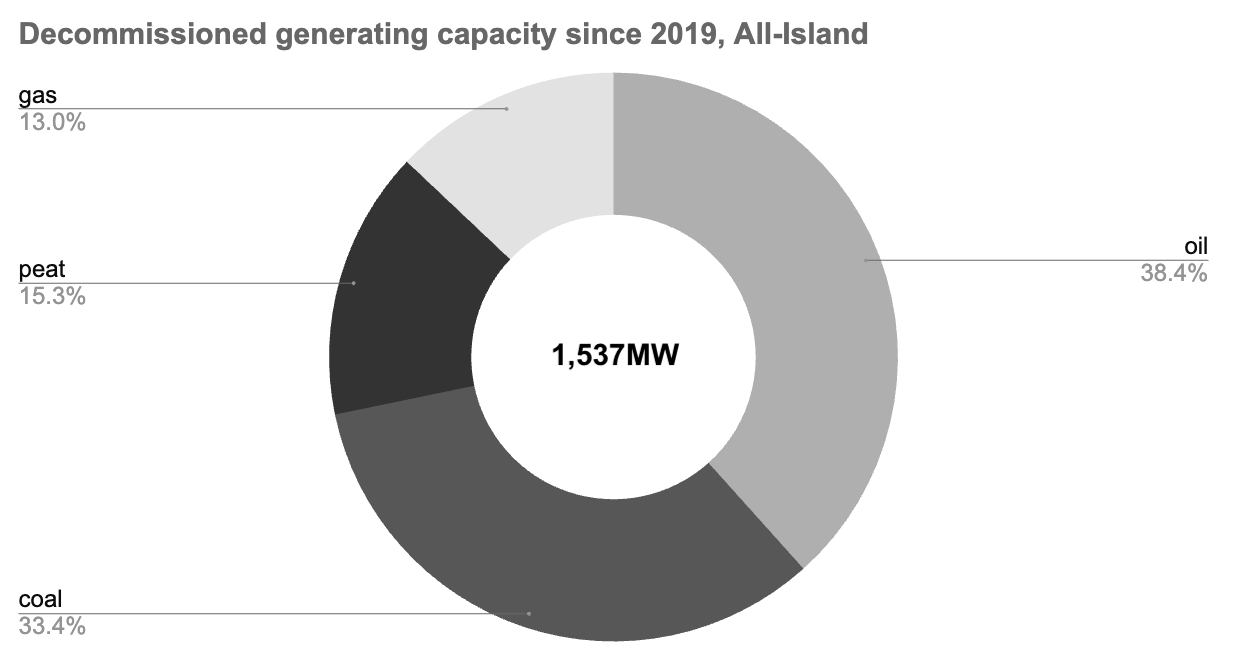

Decommissioned units and fuel switches

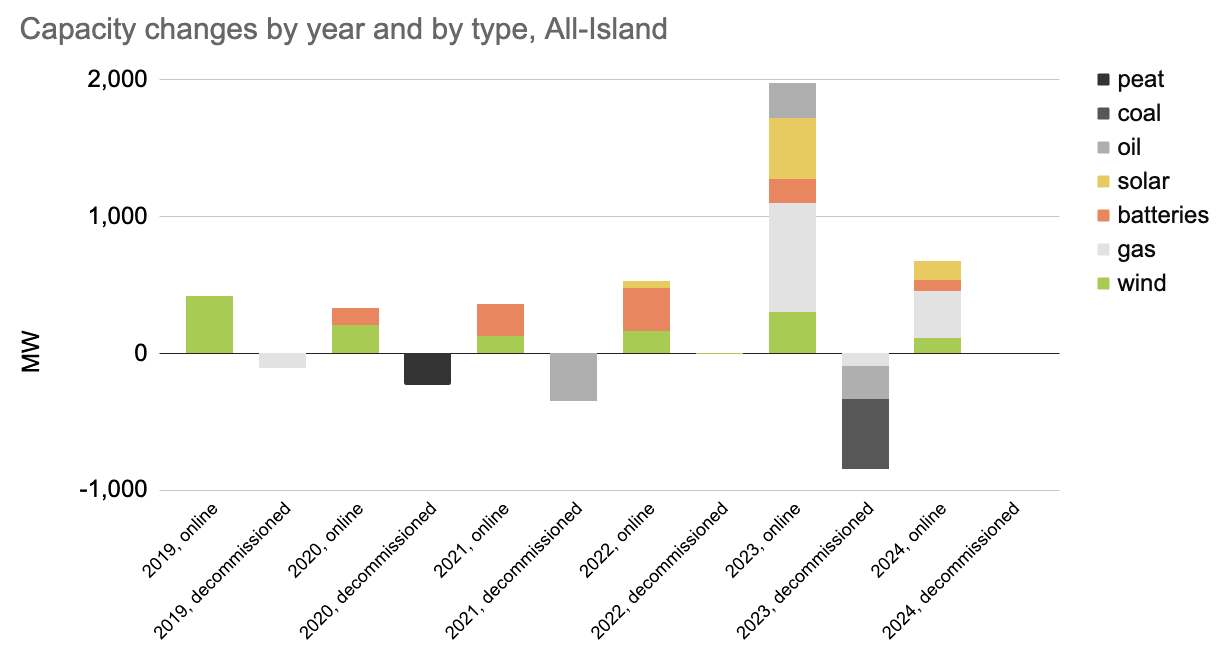

A new thing we did for this year’s capacity review is to gather data on decommissioned generators. The annually updated Generation Capacity Statements from EirGrid and SONI provide relevant details. We also cross-checked with SEMO generation data to confirm these generators’ retired status. More than 1.5GW of fossil fuel capacity has retired over the last five years. The following chart shows the breakdown by fuel type.

Exhibit 4: Decommissioned generating capacity since 2019 (all-island)

Source: Green Collective, EirGrid, SONI, SEMO

Source: Green Collective, EirGrid, SONI, SEMO

In addition to decommissioned fossil fuel capacity, there are two notable fuel switches recently:

- Edenderry switched from peat to biomass

- Moneypoint 2 switched from coal to oil

With Edenderry’s fuel switch, there is no more electricity from peat on the island - arguably, the most polluting fuel with the highest emission factors.

While more than 1.5GW of fossil fuel capacity has been decommissioned since 2019, 4.3GW of new capacity has come online in the meantime. Wind has the highest new capacity but solar and batteries have been coming online at a faster pace in recent years. Since the start of 2023, 413.4MW of wind, 580.9MW of solar, and 255MW/510MWh of batteries have come online.

The chart below shows annual capacity additions and retirements since 2019. Some of the most polluting fossil fuel units have either retired or switched fuels and new gas and oil capacity is mostly acting as peakers rather than base load.

Exhibit 5: Capacity changes by year and by type (all-island)

Source: Green Collective, EirGrid, ESBN, SONI, SEMO

Source: Green Collective, EirGrid, ESBN, SONI, SEMO

The spike in 2023 above is due to two reasons:

- the connection of multiple emergency and flexible generation units using fossil fuels in and around Dublin

- renewable projects trying to meet the deadline of RESS 1 by the end of 2023

Status of RESS 1 Projects

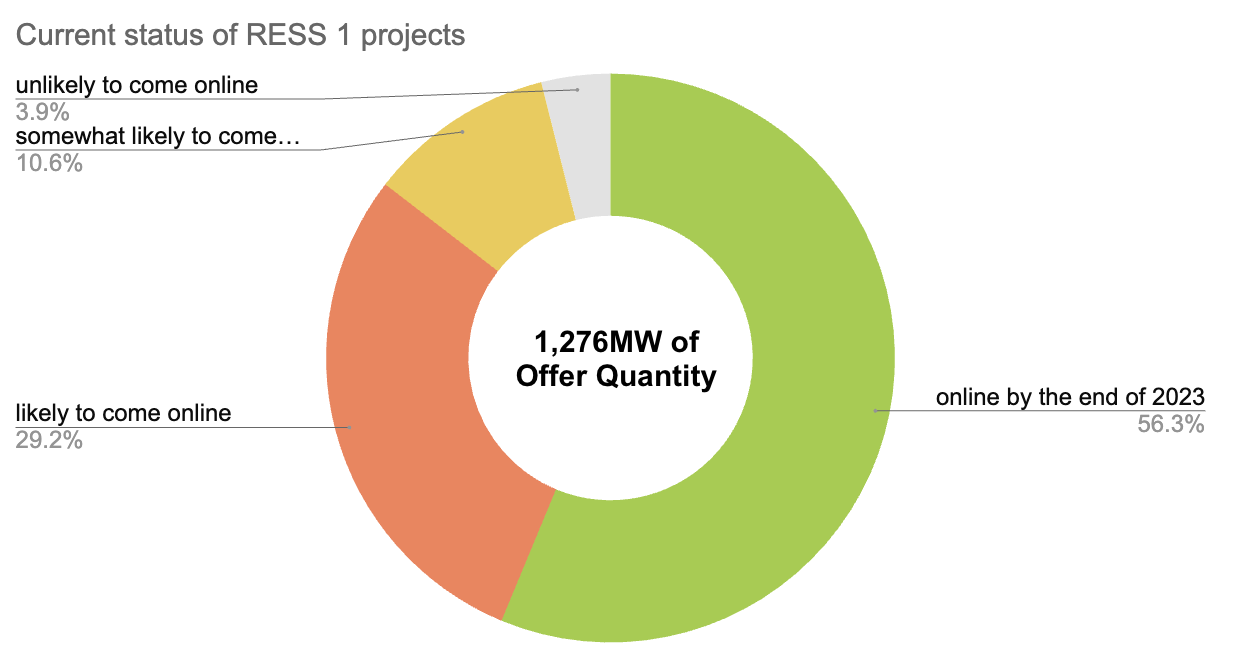

RESS rounds use a competitive auction process to determine which projects receive government support. In 2020, 82 projects (63 solar, 19 onshore wind) with 1,276MW of capacity were successful in RESS 1. We have created the following categories to assess the current status of RESS 1 projects (these could be a useful benchmark for later rounds of RESS auctions, too):

- Online by the end of 2023: Since the auction, 56.3% of RESS 1 awarded project capacity has come online.

- Likely to come online: Some are listed by either EirGrid or ESB Networks as contracted capacity, signally the likelihood to come online, even though they might not be able to take advantage of benefits from RESS 1. If these projects have a power purchasing agreement in place, benefits from RESS 1 are less important.

- Somewhat likely to come online: They are either listed as contracted capacity by grid operators or considered as firm capacity in recent ECP constraint studies, but not both. This makes their status more uncertain than the previous category.

- Unlikely to come online: Beyond the initial list from RESS 1 auction, these projects have few updates and have disappeared from contracted capacity list and recent ECP constraint studies.

The chart below provides a summary of the status of RESS 1 capacity.

Exhibit 6: Current status of RESS projects

Source: Green Collective, EirGrid, ESBN

Source: Green Collective, EirGrid, ESBN

Number of fossil fuel generators for system reliability reduced to 4 in ROI

To compile and verify a complete list of generating capacity across the island is definitely one of the more labour-intensive tasks we have taken on so far. While there are only a handful of main sources to check for updates, they certainly do not coordinate release schedules. We had the ambition to make this a quarterly report but we have had to realistically settle for an annual update.

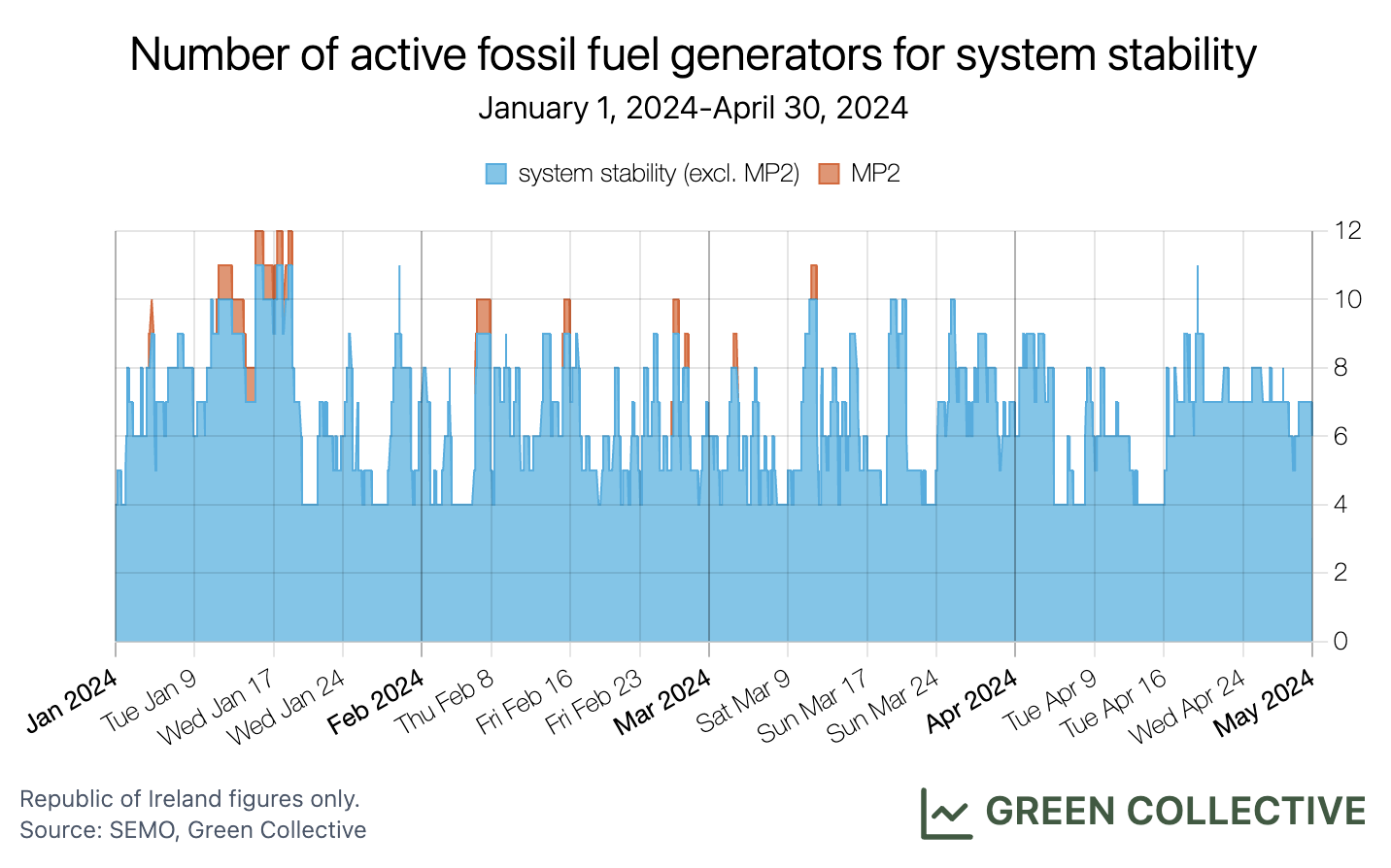

However, through this process that may or may not have made me want to scream into the void, I thoroughly enjoyed visualizing one milestone that reflects the trend towards a cleaner grid: Starting April 2024, EirGrid has reduced the minimum number of large conventional fossil fuels generators that must operate in the Republic of Ireland for system stability from five to four.

EirGrid conducted a trial from May 2023 to March 2024 to test the reduction of the minimum number of generators required for system stability. As shown on the chart below, the minimum number of four was successfully reached several times during the trial, and occurrences have been more frequent since April 2024.

We also wanted to highlight Moneypoint 2 (MP2) among system reliability resources because it shares a connection point with the synchronous condenser: this means MP2 and the synchronous condenser cannot be active at the same time. The chart indicates that MP2 is only on when when wind and solar are low and the system needs more fossil fuel units to provide generation. Otherwise, MP2 is off and the synchronous condenser is active, providing inertia the grid needs to accommodate more inverter-based renewable generation like wind and solar.

Exhibit 7: Number of active fossil fuel generators for system reliability

As mentioned earlier, MP2 recently switched from burning coal to oil, furthering its status as a flexible unit working in conjunction with the synchronous condenser while helping to reduce emissions by generating less electricity than before.

Conclusion

Overall, there is more renewable capacity - along with some more fossil fuel capacity for emergencies in the form of flexgen units. Reducing the minimum number of large conventional fossil fuel generators from five to four in ROI is such an encouraging and incredible achievement. A strengthened grid with more storage and technologies like synchronous condensers are key to enable more clean electricity on an island, which lowers the needs for fossil fuels.

While a comprehensive review of generating capacity is an annual effort, we will cover any significant updates on an ad-hoc basis both here on our website and on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Note: With the exception of distributed generation, all capacity levels mentioned in this post refer to maximum export capacity (MEC). It’s unclear whether distributed generating capacity reported by ESBN contains AC or DC values.